Wolfe Lowenthal

Oprichter van de Long River Tai Chi Circle

Wolfe Lowenthal, leerling van Cheng Man-ch’ing en auteur van drie boeken over Cheng Man-ch’ing en Tai Chi Chuan, staat aan het hoofd van de Long River Tai Chi Circle. Wolfe, geboren in Pittsburgh (VS) in 1939, begon zijn studie van Tai Chi Chuan in 1967 bij Professor Cheng Man-ch’ing in New York.

Na het overlijden van Cheng Man-ch’ing in 1975 begint Wolfe zijn eigen school en in 1977 richt hij de Long River Tai Chi Circle op. In 2002, na meer dan 25 jaar in New York les te hebben gegeven, verhuist hij met zijn vrouw en twee kinderen naar Amherst, Massachusetts (VS) waar hij nu nog steeds woont.

In de Verenigde Staten heeft de Long River Tai Chi Circle scholen in de staten New York, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont en Oklahoma.

Een quote van Wolfe:

As children we are grounded and relaxed into the earth. As we age, we become progressively less connected to the ground. Our legs weaken and we become top-heavy and tight in our upper body. This produces a lack of balance and disharmony in our internal organs. Tai Chi Chuan reverses this process.

We learn how to be like a child again, sinking our energy to the tantien, regaining good balance and allowing our legs and the ground to support us. We can begin this relearning process on our first day of study, and improve on it as long as we live.

As we relax, we allow the energy in our internal organs to become free-flowing and harmonious. We free the blocks to our circulation, and reverse the progressive weakening of our bones, so that they become essentially strong.

Van 2000 tot 2010 kwam Wolfe in de zomer naar Europa om een intensieve workshop met zijn Europese leerlingen te geven. De zomer workshops worden sinds 2011 in Amherst, VS gegeven.

Meer informatie over de drie boeken van Wolfe kun je hieronder lezen.

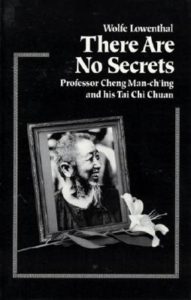

There Are No Secrets

What we play with in push hands is at the core of many of our relationship problems. During push hands class the following conversation is common:

What we play with in push hands is at the core of many of our relationship problems. During push hands class the following conversation is common:

First Student: “You’re too hard, you’re pushing on me like a freight train!”

Second Student: “Well, you’re not soft, you’re not yielding at all; you’re like a brick wall!”

All push hands players have experienced this conflict. Its lesson is that if in pushing I find my partner straining in resistance, the fault also lies with my use of strength – if I were not being so insistent he could not resist me. Conversely, if I feel my partner’s hard force building up on my body, it is because of my resistance – if there were no resistance he would have nothing to push against. “It takes two to tango”; in push hands, a fight or life, conflict is based on an agreement between the two parties.

Professor Cheng addresses this problem in his Thirteen Treatises: “When two people work a saw, their strength must be even so that there is no resistance in the forward and backward movement. If one side changes the balanced strength just a little, the teeth of the saw may get stuck. If the opponent lets the saw get stuck, I cannot keep going backward and release it by any amount of effort. I must first send it forward in order to resume the former motion.”

“Give up oneself in order to follow others. When one can be in accord with the force, one can attain the wonder of neutralization.”

“If the opponent moves only slightly, I shall have preceded the move. In other words, if the opponent uses force to press forward, I have already pulled back. If he has used force to pull back, I have preceded him sending my energy forward.”

The hardness, egotism and willfulness underlying conflict also has health implications. In his commentary on Lao Tzu Professor said, “If one’s will is too strong, it will not only harm one’s primal energy, but will also harm the very root and trunk of one’s life span.”

Gateway to the Miraculous

“There are no secrets in the Tai Chi Chuan that I am teaching you,” said Professor Cheng, “but if there were a secret, it is that the mind moves the ch’i.”

“There are no secrets in the Tai Chi Chuan that I am teaching you,” said Professor Cheng, “but if there were a secret, it is that the mind moves the ch’i.”

Sometimes he would say, “There are no secrets in this Tai Chi Chuan, but if there was a secret, it is that the hands don’t move.” This was yet another one of those times when I initially thought he was contradicting himself, only to realize later that in both cases he was saying the same thing: “The hands don’t move” and “The mind moves the ch’i” are the same and the secret of our Tai Chi Chuan.

“The hands don’t move.” It is rather the mind, or more precisely the idea that directs the waist to produce the movement. The energy only emerges from the hands, which move from the waist like spokes on the hub of a wheel.

“The waist is the commander,” it says in the Tai Chi classics, and the hands should submit totally to the command of the waist – never moving independently.

Like a Long River

Professor’s teaching is a beacon guiding us away from the denial of life to the understanding of the chi, the life force. That understanding leads us beyond even the virtues of health, well-being and self-defense.

Professor’s teaching is a beacon guiding us away from the denial of life to the understanding of the chi, the life force. That understanding leads us beyond even the virtues of health, well-being and self-defense.

It leads to the life affirming freedom of the Tao.

It is Professor Cheng’s greatest legacy.